Are Recent Valuation Hits as Unreasonable as they seem?

I believe in fundamental valuations. What is something worth? The whole thing, not just a piece of it and not just in a fortuitous…

I believe in fundamental valuations. What is something worth? The whole thing, not just a piece of it and not just in a fortuitous strategic buyout scenario. As a finance geek and an engineering nerd, I have been questioning the many accepted definitions lately. But is it possible to understand absolute valuation in a vacuum? Is everything relative, creating a seemingly unsolvable circularity? Is the price of a small piece representative of the value of the whole? Does the security need to be liquid to know anything for sure? The answer in most cases lies somewhere in the gray area.

On a theoretical level, the discounted cash flow analysis provides the best proxy for what something can pay you, and therefore what it is worth: on a net present value basis, what is the combined value of the expected future cash flows of a business. Given that most operating companies don’t pay all their cash out to their shareholders and that long term projections are often unreliable, there is a large gap between the theoretical pay out and what actually gets paid to equity holders. In addition, rapid growth and variable margins present big issues when trying to perform a DCF valuation. There are also so many independent variables (Beta, cost of debt, market risk premium, long term growth rate, etc.) in a DCF analysis that it’s tough to get an accurate valuation instead of just a precise one.

Another key valuation method is the Price to Earnings multiple: start with Net Income and apply an industry-appropriate multiple to determine the appropriate valuation for the company. The high level idea is that shareholders are willing to pay a certain amount for each dollar of net income that could, in theory, come to them in the form of an ongoing dividend in the future. Growth rate, future profitability, market changes, and acquisition prospects all factor into that multiple that is applied to Net Income which results in the valuation. Because Net Income is the last line on the income statement, it incorporates all of the operational aspects of the business, and therefore is a good representation of the current state of the business as a whole.

But when trying to value a company with negative cash flow and negative net income, what metrics should you use? A few options are Free Cash Flow, EBIT, EBITDA, Gross Profit, Revenue, Bookings, or some combination of these. The reality is that many rapidly growing companies are trading on forward revenue. Why? Because comparable companies are at vastly different stages of profitability, revenue growth is the differentiator, and in many cases, it’s the only number with a meaningful positive value. If you assume a “standard” trajectory towards profitability, you can apply a multiple to the near-term revenue, which, if all goes well, should correspond to a positive net income multiple many years in the future when the company matures. Enough companies have gone from high growth & unprofitable to moderate growth & profitable that when investors see the right early indicators (bookings growth, SaaS magic number, net churn, unit economics, etc.), they assume a similar “standard” trajectory towards profitability and therefore the associated multiple of the current revenue. This concept is something we know and take for granted: a fast growing company with promising early operational indicators will get valued based on its current revenue and expected growth, although I don’t think many investors are actually doing this calculation on paper (nor should they).

So why then, if a company lowers revenue guidance by 1% can the stock price go down 40% or more?

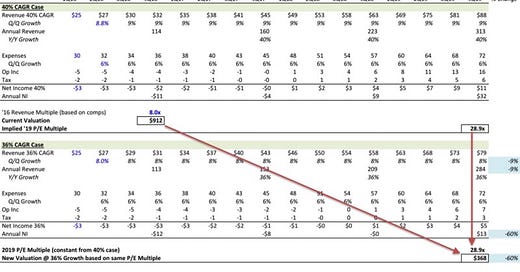

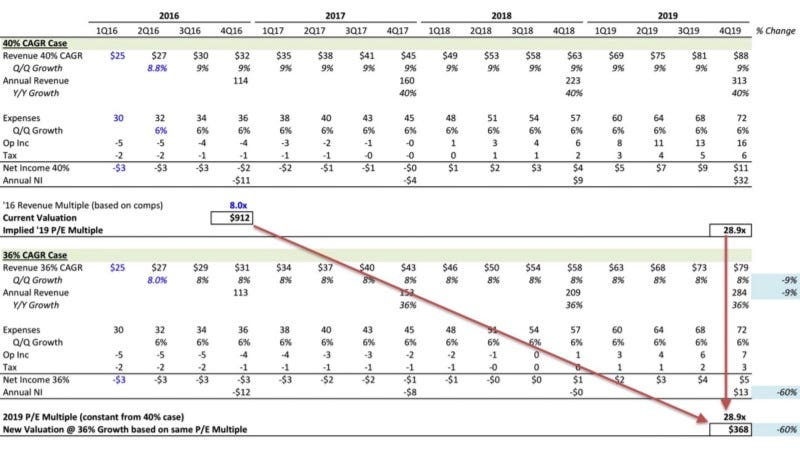

I’ll illustrate it with an example. We are currently in Q1 2016. If revenue guidance for Q2 is lowered by 1% and that 1% decrease continues going forward, then 4 years down the road, the impact on revenue is ~10% annually. But if expenses do not change accordingly, the future impact on the net income line can be disproportionate for a currently unprofitable company. The compounding effect over 15+ quarters can result in a massive decrease in the valuation if you assume the same P/E multiple 4 years down the road. An example with some real numbers: A company is projecting 8.8% quarter over quarter revenue growth and then lowers guidance to 8% (36% annual growth instead of 40% annual growth). 15 quarters later, the quarterly net income is 55% lower than it would have been otherwise (assuming unchanged expenses). Meanwhile, revenue is only 10% lower. This is the case investors are afraid of: a small change in revenue growth and no change in expenses can push the point of profitability out several quarters or years.

Below is a chart that illustrates these two cases:

Note that a change in the revenue or expense margin impacts the relative growth of the valuation gap, but the overall effect stays the same.

So while right now these growing, unprofitable companies are valued on a revenue basis, it’s clear that this is based on the expectation of profitability in the future. This offers an explanation to why a 10% change in the current key valuation metric, revenue, can result in a much larger change in the stock price: stock price is tied to future net income more than it is tied to revenue.

Further, any decrease to revenue guidance is compounded twice by the time you arrive at net income 4 years out: one time for each run through the income statement (the revenue line all the way down to net income line) and a second time each quarter. It’s like taking a double derivative in calculus — it’s extremely small angle approximation. To put it in practical terms: unprofitable high growth companies are walking on thin ice with regard to achieving their projections.

Most investors are not using these specific calculations (or anything like them) to value companies (often because these numbers are too difficult to project), but on a high level I am simply attempting to associate numbers with the key factors — near term growth & long term profitability — that impact the present valuation of a company.

The question might arise: why can you assume that a 1% decrease this quarter means the same for next quarter? The answer is the same reason these companies are valued so richly in the first place: recurring revenue business models, which result in highly predictable future revenues. A dollar of revenue lost today is also not there next quarter and every quarter into the future (in the same way that a new SaaS contract is expected to provide revenue in perpetuity). If the reason for this lost dollar is an inefficient sales process, worse than expected product-market fit, and/or a smaller market, then it’s fair to expect that this 1% decrease will be sustained into the future and compound every quarter. When the markets are fickle, investors are much less likely to assume an earnings miss or a guide down is an anomaly, and an alarm goes off that the fundamentals of the business itself are not as promising as expected (and it has erred from the “standard” trajectory). The lack of consistency in the markets is yet another compounding factor. Because investors are betting on numbers far into the future and a small change today can have massive repercussions for future profitability, a seemingly small change in guidance has a punishing effect on share price — something we have all seen and felt acutely over the past week.