A quick idea on writing down venture investments...

Preferred stock investments work differently from common stock investments. This is absolutely critical to understand when calculating holding values.

When a company gets "written up," it is common practice to take the latest (and highest) preferred share price and apply it to all holdings (common, options, seed, Series A, etc.). This is actually not accurate. Because of seniority in liquidity stacks and the wide range of possible outcomes, Series D shares are worth more than Series A shares (for example).

Exactly how to apply that discount is an entire discussion on its own and is in the realm of secondary investing experts.

When it comes to writing investments *down*, it's important to remember that it only makes sense if either:

A) you previously wrote it up and the company raised subsequent financing at a lower share price than you had written it up to.

or

B) the company is worth less than the size of its liquidation preference as it relates to your investment.

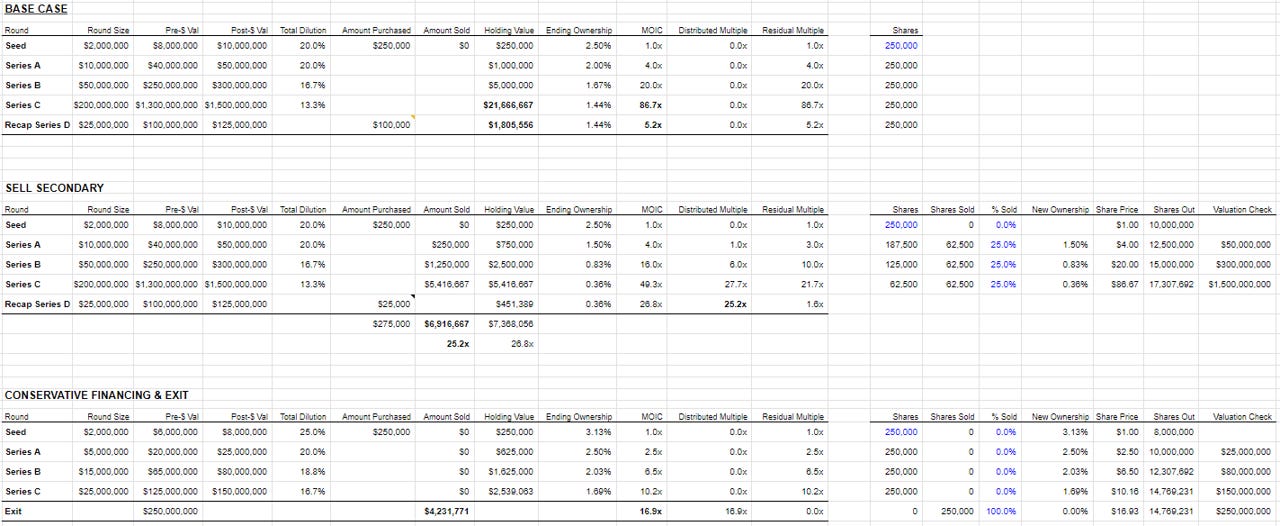

If you invested in a company at $1 per share, then it raised at $3 per share, you're probably going to write that up 3x. If after that, it raised at $2 share ... then we get some complexity. Most likely given how liquidation stacks work, your true holding value will be slightly below that $2 per share. This all depends on the details of the financings themselves.

If you invested at $1 per share and the company has not raised any additional capital, there is no reason to write down that investment unless you think the value of the company is less than the size of the financing you participated in. That means if multiples have come down in the market or the company has not hit growth targets, but it is NOT in danger of becoming insolvent, there is no reason to write down this investment.

A practical example: you participated in a $25M financing at $150M valuation. The company has $20M left in the bank, but is only at $4M of revenue. The question is not whether the company is still worth $150M (I have made many arguments that it never really was), rather it is whether the company is worth more than $25M: if it is, then you still hold your investment at cost.

You will make your principal investment back at any outcome between $25M and $150M. Above that you have a positive return, and below that negative. This is where misaligned incentives occur:

If a founder wants to keep going for another 2 years to try to get to $15M of revenue, the result for the investors in that $25M on $150M round will likely be the same ($150M exit, they get 1x their money back - excluding any additional financing needs). But for the founder, it makes a huge difference. Let's say they own 20% of the company, that is the difference between the founder earning $30M and $0. But the investors may prefer to just get their money back now because the chance they make meaningfully more is low enough and will take long enough that they think it's just not worth it to risk their principal investment. This is another reason why high valuations are more likely to put companies in a bad position than a good one. If the round was done at $75M post, those same investors would be looking at a 2x, which is a big difference inside a fund.

Additional thoughts on this subject:

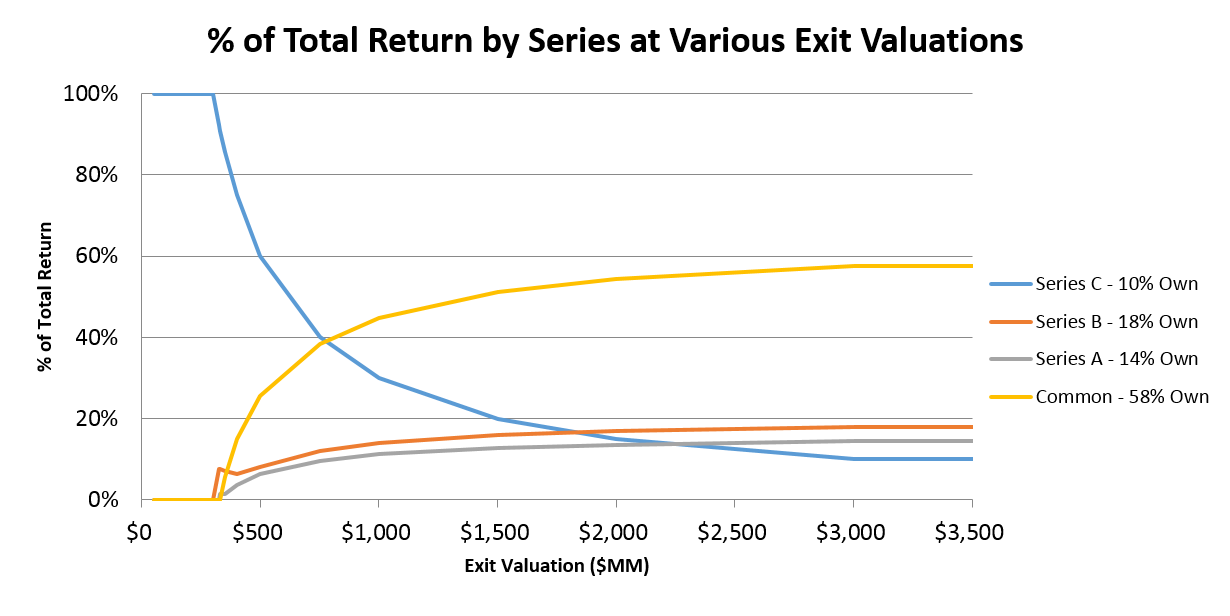

You pick the Valuation, I set the Terms…

This is an old adage in the world of venture investing that represents the potentially massive disconnect between the “valuation” on the term sheet and the returns in various exit scenarios. I put “valuation” in quotes because of this disconnect. How often do we read “XYZ company has achieved a $1Bn valuation” or “ABC company is now worth $2Bn” or somet…

How are SaaS Startups Valued?

I get asked this question all the time. There’s no doubt that the SaaS business model has dominated the last decade (do I even need to list out the SaaS subscriptions you probably paid last month?). And we’re all the better for it: SaaS is good for the world - customers can churn, which keeps companies developing new products and providing quality servic…

How to mess up a good company and not make any money along the way

I wrote previously about the various ways to be wrong in investing here: https://alexoppenheimer.substack.com/p/expensive-options-and-losing-big And I wrote about investing in turbulent markets here: https://alexoppenheimer.substack.com/p/capitalization-and-financing-for

Valuation and Primary Capital

The capital markets are starting to settle down after the most aggressive venture investment environment ever. The amount of capital deployed in 2021 was absolutely astounding at over $300Bn… and that is just what got announced. As with any massive influx of supply into a market, price goes down. In this market, the

Very interesting and insightful! Definitely depending on the stage of the company you'd rely less on DCF and perhaps more so on public comps and txn. comps however you also have to keep in mind the DLOM (discount for lack of marketability). I actually put together a linear regression for valuing based on public comps. Happy to share my model and outline (im at katarinapetruzzo@gmail.com).